translationCore is an open source platform for checking and managing Bible translation projects. tC provides an extensible interface that enables, among other things, systematic and comprehensive checking of Bible translations against multiple sources and the original languages with just-in-time training modules that provide guidelines and instruction for translators.

translationCore is in active development, but you can still download the latest version of translationCore if you want to try it out.

You can also download a zip file of the translationNotes tC checks. These are tab delimited files that you can use for manually checking a translation.

translationCore: a Platform for Precision

translationCore is an open-source, open-access, cross-platform software tool that enables comprehensive checking of Bible translations. (NOTE: Technically, translationCore is a modular platform that is highly extensible and will soon provide far more functionality, including management of content repositories, translation teams, publishing, etc. Its primary use is for checking). It integrates with the Door43 Content Service and is designed to easily work with other Bible translation software (including translationStudio) and ParaTExt).

It is designed to provide a real-world implementation of the theoretical framework described so far in this document. That is, translationCore attempts to freely provide each ethnolinguistic Church with comprehensive checking resources that enable the Church to confidently and reliably confirm and improve the accuracy of their own Bible translations (“trustworthy”) by applying the principles of excellence in Bible translation (described in translationAcademy) and enabling the comparison of their translations against multiple sources and the original languages so that the Church can confidently rely on their Bible translation (“trusted”).

Component Pieces

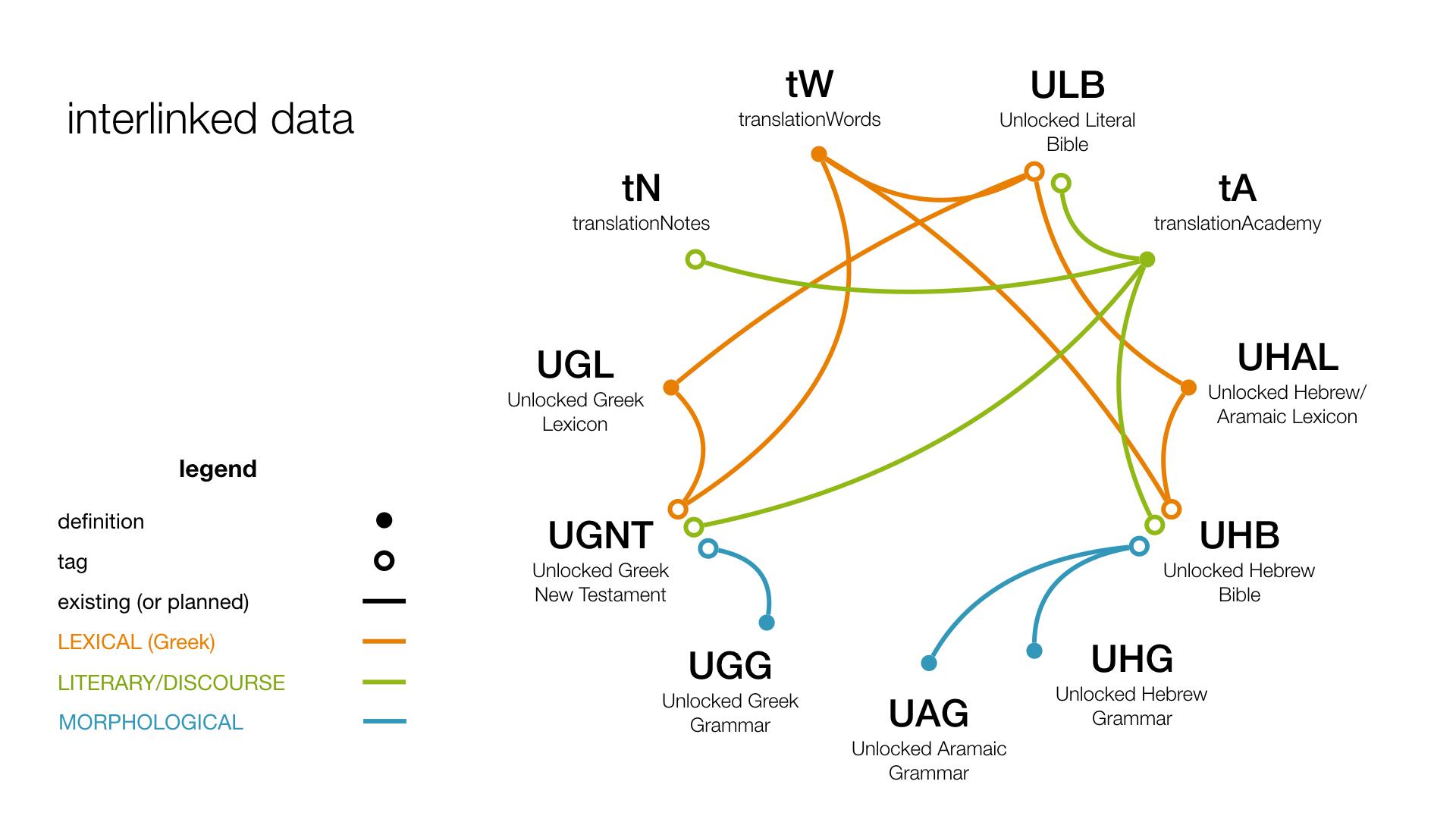

translationCore uses structured, open-source biblical and exegetical resources to provide the checking framework and comprehensive checklists. These resources have two levels of value to translators: the data (the words that are visible in the resource) and the metadata (usually in the form of “tags” that provide computer-usable data about the words themselves). By using tagged data, translators see not only the content but also how the content is connected to other content.

The resources used in translationCore include:

-

Unlocked Literal Bible (ULB) — An open-licensed update of the ASV, intended to provide a “form-centric” understanding of the Bible. It attempts to increase the translator’s understanding of the lexical and grammatical composition of the underlying text by adhering closely to the word order and structure of the originals. In progress: tagging the text according to the lexical roots of the original languages.

-

translationNotes (tN) — Open-licensed exegetical notes that provide historical, cultural, and linguistic information for translators. The exegetical data is tagged, connecting it to information pertaining to key terms (translationWords), translation and checking principles (translationAcademy), and linguistic information about the text. For example, every metaphor is tagged in the metadata, as are other literary devices (e.g., synecdoche, metonymy, double negatives, etc.)

-

translationWords (tW) — A basic Bible lexicon that provides translators with clear, concise definitions and translation suggestions for every important word in the Bible. In progress: tagging the text according to the lexical roots of the original languages.

-

translationAcademy (tA) — A modular, tagged training resource intended to provide clear instruction with examples regarding the principles of Bible translation and checking, as affirmed by the global Church. In progress: 6th revision

-

Unlocked Greek New Testament (UGNT) — An open-licensed critical Greek New Testament with full apparatus, lexically tagged, morphologically parsed. In progress: merging and extending existing public domain texts, second revision of critical text.

-

Unlocked Greek Lexicon (UGL) — An open-licensed Greek lexicon, lexically tagged. In progress: merging and extending existing public domain lexica.

-

Unlocked Greek Grammar (UGG) — A Greek grammar (reference first, eventually for teaching), providing information about Greek grammatical elements. In progress: initial resource design

-

Unlocked Hebrew Bible (UHB) — An open-licensed Hebrew Old Testament, lexically tagged, morphologically parsed.

-

Unlocked Hebrew and Aramaic Lexicon (UHAL) — An open-licensed Hebrew and Aramaic lexicon, lexically tagged. In progress: initial resource design.

-

Unlocked Hebrew Grammar (UHG) — A Hebrew grammar (reference first, eventually for teaching), providing information about Hebrew grammatical elements. In progress: initial resource design

-

Unlocked Aramaic Grammar (UAG) — An Aramaic grammar (reference first, eventually for teaching), providing information about Aramaic grammatical elements. In progress: initial resource design

This diagram shows how the metadata in each project works together:

How it works

When using translationCore, the translator (or whoever is doing the checking) begins by choosing a project to check. A translation of any complete book of the Bible can be selected (and support for multiple books, including the entire New Testament or Bible is planned). With the translation project selected, the translator selects a check to perform on it, e.g., “Lexical Check”.

Based on the project to be checked (including the sources used) and the kind of check selected, translationCore analyzes the source content and builds a set of checklists. In our example, translationCore would analyze the source translation used (e.g., English ULB) and parse it lexically (using translationWords) to identify every word in the source text that should be checked. It arranges the list alphabetically by the word to be checked.

For example, the word “grace” may occur in 8 verses in the selected book. Each reference would be displayed as a hyperlink under the term that, when clicked, loads that verse on the screen. The translator can see the source content (including in the original language and with the lexical definition and parsing, if desired), their translation of the verse, and the definition of the word (as well as translation suggestions) from the entry for “grace” in translationWords. The definition (and parsing) would appear in the translator’s preferred Gateway Language, once all of the resources have been translated.

The translator then clicks the word (or words) in their translation that corresponds to the word in the original. This simple tagging process creates a data mapping that translationCore will use later for everything from generating a list of all translations of the word “grace” used across the entire book (or Bible) to automatically creating a concordance and Bible lexicon in that language as well.

After selecting their translation of the word “grace”, the translator indicates if their translation of that word was “correct in context” or if they want instead to “flag for review”. In the event the word was translated incorrectly or misspelled, they can indicate the correct word or spelling and also add a note about the translation of that word in that verse.

Once the translator is familiar with the workflow, the entire checking process can take as little as a few seconds for each word. As they progress through the rest of the words that need to be checked, the status of each checked verse (the checklist) is displayed for the translator’s reference and review.

Reporting

All the data pertaining to the checks performed on that book are stored together with the translated text. This makes it possible to perform multiple checks by multiple checkers on the same verses. The checking information can be aggregated into a comprehensive report of what was checked, when, by whom, for each verse.

Applying changes

Whenever desired, the translator can review all the changes they intend to make to their translation and apply those changes directly to the translation. (NOTE: This creates a revision of their translation in the content repository, so they are not overwriting any information and can roll back any changes at any point, if that is needed.) The translationCore engine will attempt to make the changes automatically, but where proposed changes overlap (e.g., changes proposed to a metaphor and changes also proposed to a word in the metaphor), the translator can update the verse manually, if needed.

Publishing and Revisions

The translator may choose to apply many different checks to their translation, including, for example, a Discourse Check, a Literary Devices Check (i.e., metaphors, double negatives, etc.), and a Lexical Check. Once they have performed the desired checks and applied the changes, they may choose to publish their work.

An important aspect of the publishing process is the generation of the changelog—the list of every verse that changed since the previous revision. The intent of publishing from translationCore is to make the list of changes, optionally including the reason for the changes, transparent to the reader of the translation.

Extensible Checking

The design of translationCore is extensible, meaning other checks can be created by anyone, for any reason. Certain standard checks (like those listed above) will be included by default, but the design of the platform intentionally enables Church leaders to create new checks, as desired. For example, they may want to have a “Hindu Cultural Check” to ensure that translations correctly handle verses that address Hindu cultural issues. It would also be possible to create theological checks that cover, for example, all passages in the Bible dealing with soteriology (or Christology, baptism, eschatology, etc.).

A Future of Possibilities

The flexible, multilingual, and data-driven design of translationCore suggests many other possibilities that could be built on it. Some examples include:

-

spell-checking — Manual (or even semi-automatic) spell-checking is already included in translationCore lexical checking and it could be extended to provide automatic spell-checking.

-

Bible study tools in any language — Because of the ease with which data tagging is possible, the creation of data-driven Bible study resources will be greatly simplified in any language. Bible lexicons, concordances, and handbooks would be relatively easy to provide, both digitally and in print.

-

Bible study tools in many languages, simultaneously — These Bible study resources would not only be available in one language, but could be made available in multiple languages. This could include the original texts, languages of wider communication and minority languages. Assembling the resource could be as simple as going through an online assembly process (similar to a shopping website) where the user may select resources, languages, layout, and format (e.g. print-ready PDF), all for free.

-

group translation checking — An effective means of checking Bible translations is to do so in a group setting, where multilingual speakers with shared cultural elements can provide insights into translation choices that may be useful in other contexts. The design of translationCore could enable Church leaders to help check the work of many translations in parallel.

-

advanced Computer Assisted Translation of biblical content — One of translationCore’s most promising possibilities is the use of tagged Bible translations as the inputs to programmatically generate translations of new biblical content. Research is ongoing but early results are promising, indicating that once a Bible translation has been aligned during the checking process, alignment from source tags to target tags allow the engine to pre-populate biblical resources for the target language, helping to optimize it for use as a source language.